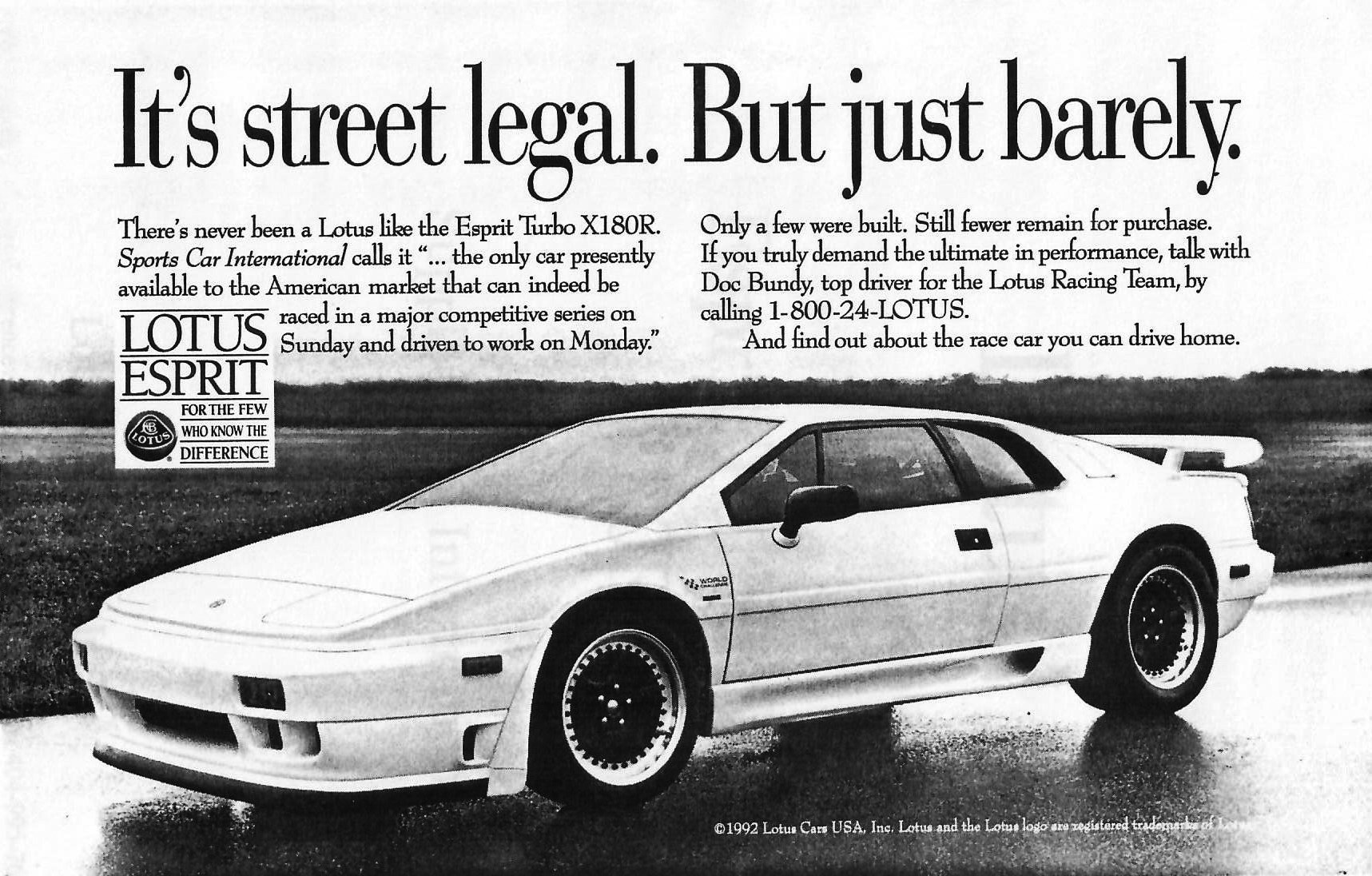

Imagine walking into a Chevrolet dealer and driving away with a new factory-built Corvette C8R racecar that was street legal, as well as virtually ready to race and win. Today, you can’t buy a caged factory-built turn-key race car that is road legal in the United States at any price. But 30+ years ago, you could buy a Lotus Esprit X180R.

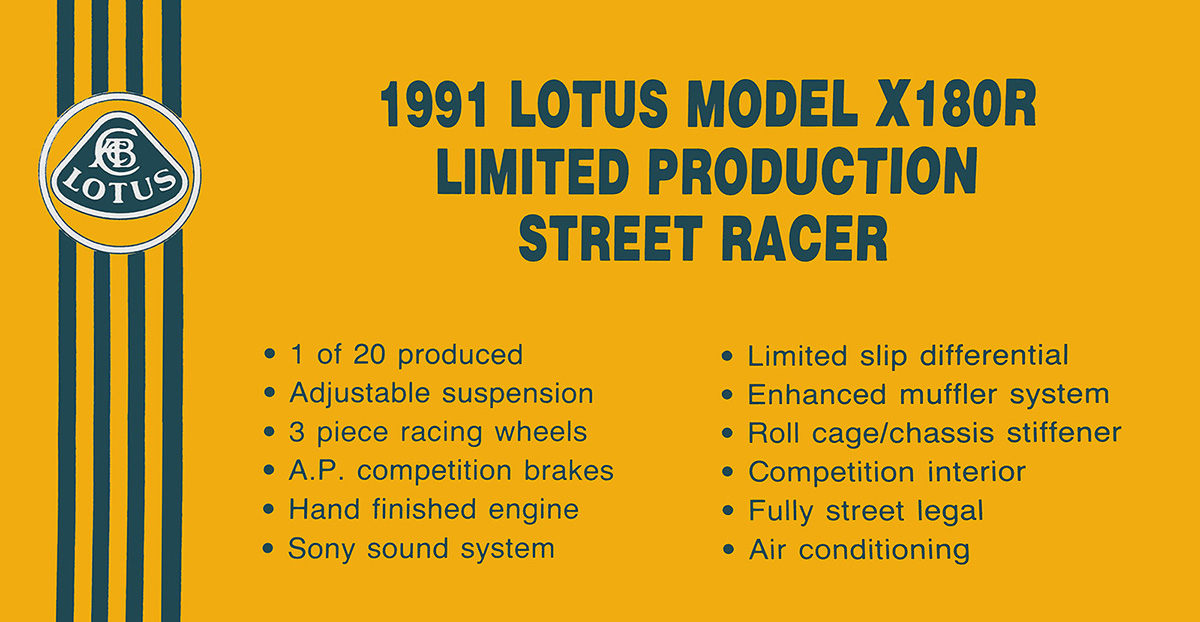

With only 20 road-legal homologation cars produced and five SCCA/IMSA factory prepared race cars, the X180R was unlike any other Esprit model produced. Straight from the Lotus factory, the X180R was a highly-developed race car for the road that included a chassis-integrated roll cage, fully adjustable racing suspension, blueprinted engine, specialized and deleted parts for significant weight savings, and a variety of other competition upgrades. Looking back 30 years later, Lotus’s X180R was the last factory-built race car with a full roll cage — from any manufacturer — that was sold new in the United States and could be licensed for the street. The only car that came close, was the 1995 model year Ferrari 355 Challenge, which was a street 355 that an authorized dealership would convert into a race car using a kit provided by the factory.

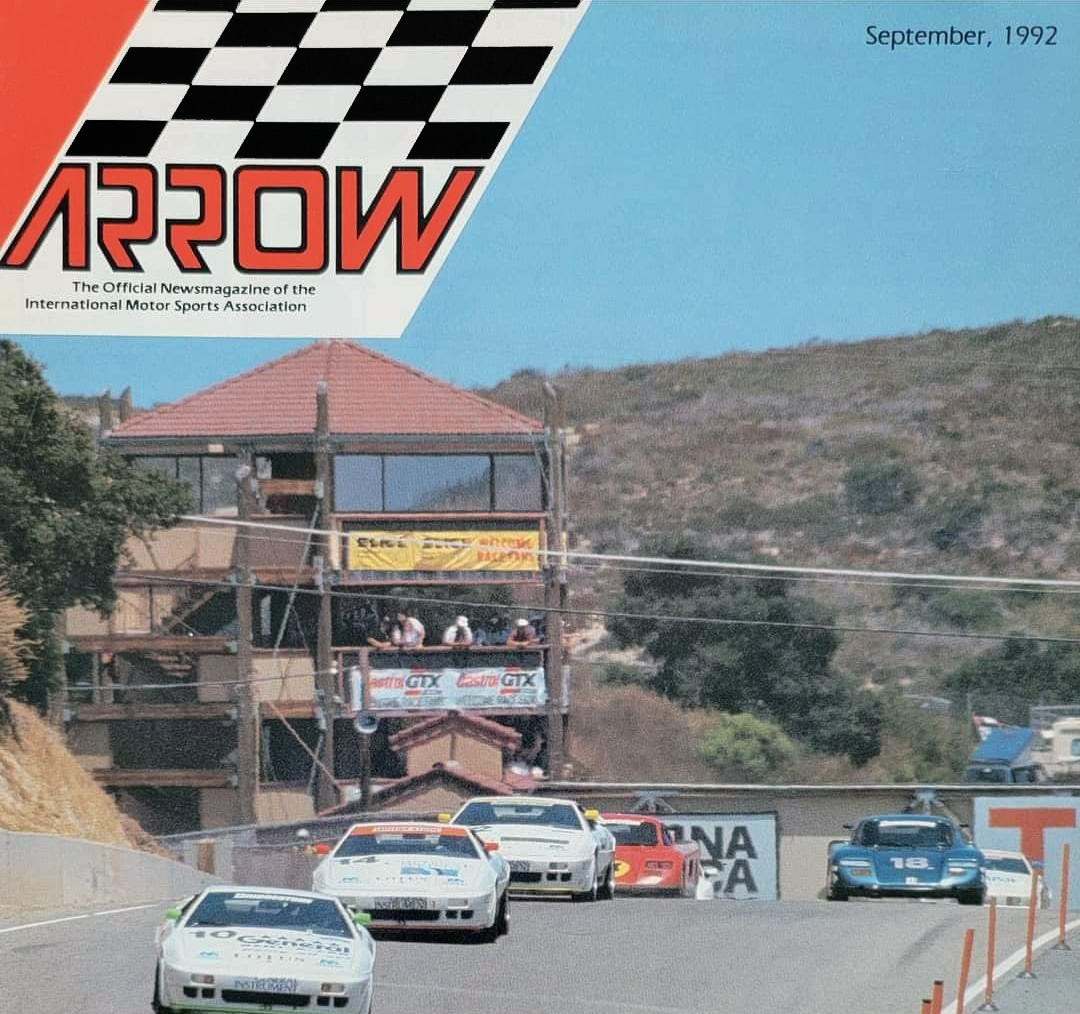

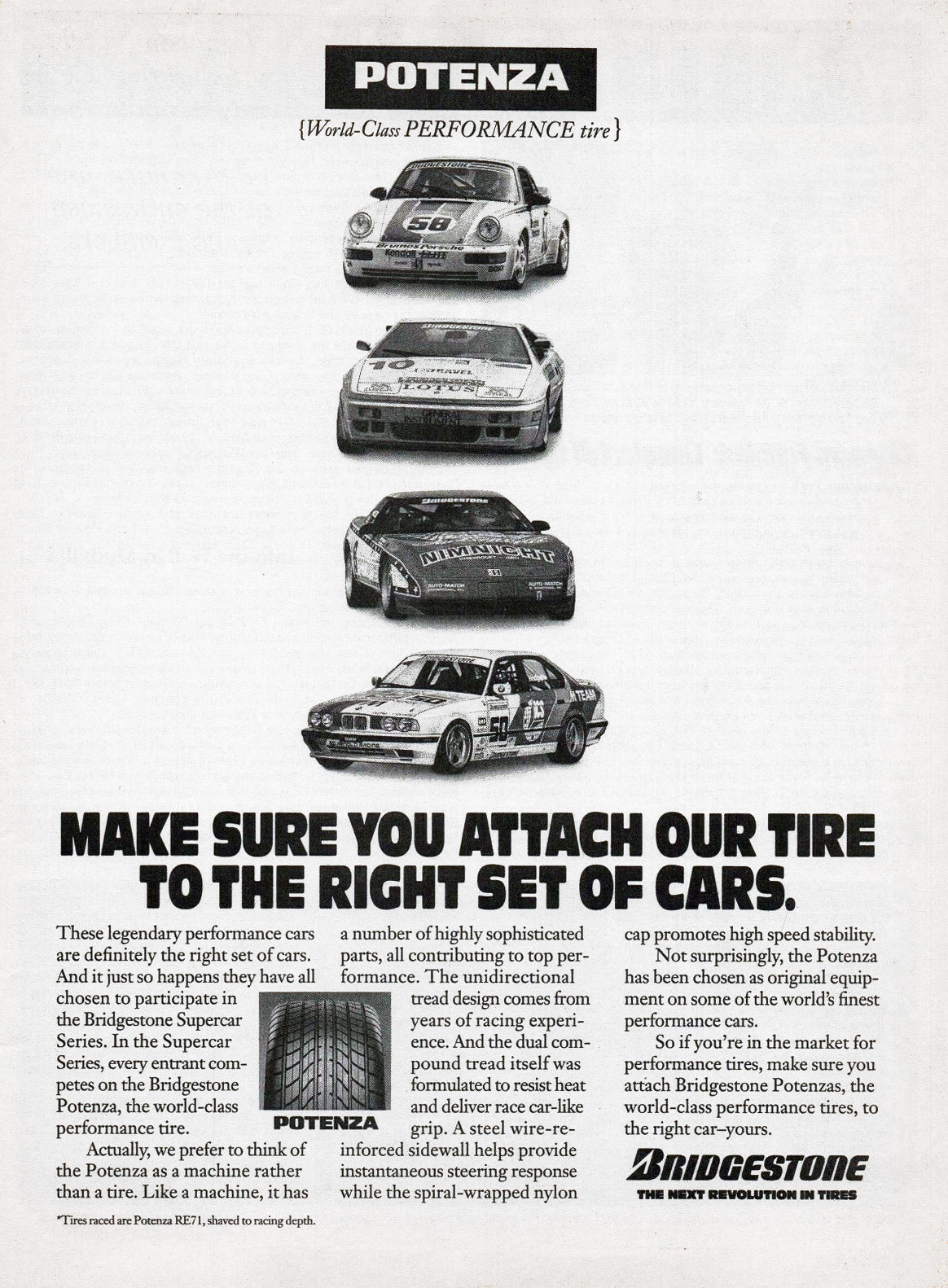

There were three distinct variations of the factory-built race-ready Esprits. First came the Type 105 World Challenge race car which resulted from the factory converting two production Esprit SEs for racing in the SCCA World Challenge series. Next, to homologate the X180R for IMSA’s new Bridgestone Supercar Championship series, Lotus created the required twenty North American “race replica” models necessary to race in the championship. Standard Esprits fulfilled the other homologation production requirements. For marketing purposes, Lotus touted its previous year’s World Challenge series championship to excite buyers into understanding the special model, and even applied the “World Challenge” flag logo to the X180R’s front fenders. The final variation—of which only three were built—was the Type 106 IMSA race car, based on the X180R homologation car as IMSA’s rules required minimal deviations from the street model. In its first full Bridgestone Supercar Championship season, the X180R took both the driver’s and manufacturer’s championship titles, battling heavily against Porsche’s efforts to repeat their victory from the previous inaugural season. IMSA continually added substantial weight penalties to slow the X180R. Since the Bridgestone Supercar series was designed to keep cars competitive by trying to normalize performance, the Lotus continued to compete well with many pole positions and wins, however additional overall championships proved elusive.

World Challenge Racing – Origins of the X180R

In the late 1980s, SCCA had found success with its televised single-marque Corvette Challenge series. For the 1990 racing season racing season, SCCA decided to change the rules for the professional series to open it to non-Chevrolet models and renaming the series “World Challenge.”

This new professional racing series was designed for production-based sports cars with a limited set of modifications for racing. Looking at this as an opportunity, racing driver Doc Bundy pitched the idea of entering the SCCA World Challenge to Lotus as a way to better promote the company’s high-performance cars in North America and showcase the Esprit’s performance against its peers. David Murry, one of the LotuSport team drivers, recalled “Doc was on the Corvette GTP team with Hendrick Motorsports, and they had a Lotus active suspension on that car. When that whole program went away, Doc went to Lotus in England and said you guys need to showcase your actual street cars in a race series." Lotus Cars Ltd and its North American branch Lotus Cars USA agreed, although it could be a risky move as a failed attempt might hurt sales. The resulting serious development of the Esprit by Lotus factory enginers was crucial to ensure this would not happen.

Lotus, a company founded on Colin Chapman’s engineering skills and his enthusiasm for racing, quickly formed a plan that pulled two Esprit SEs off the assembly line and sent them to Lotus Engineering for development. Although the Esprit was never designed as a racing car, Lotus quickly focused on developing the platform into a competitive racecar. Internally designated the Type 105, the new racing Esprit model would be substantially lightened and fitted with upgraded components.. Roger Becker, Lotus development engineer and test driver, commented that the initial planning for the Type 105 specifications took “about a week, but we had a lot of parts in place from our lightweight programme and our office [did] know an awful lot about the Esprit chassis." He had long wanted to develop a lightweight Esprit capable of fighting Porsche’s 911, so when the Type 105 received the green light, much of the work had already been completed.

The team was able to drop the stock Turbo SE’s 2,907 lbs weight down to approximately 2,500 lbs in Type 105 specification, while raising power from 264 hp to 285 hp.

Once the first Type 105 was complete, Lotus engineer and former Team Lotus F1 driver John Miles worked on the development of the car, including testing of the ABS system at GM’s Milford Proving Grounds but most on track development work was carried out by the Pure Sports team. Other Lotus personnel involved in the project included former TWR mechanic Colin Marriott and and transmission expert Alan Nobbs.

Roger Becker recalled, “We took the air conditioning out, but took advantage of the condensor to plumb up extra direct-feed capacity for the standard chargecooling. This allowed us transient horsepower readings in the region of 300 bhp and the motor proved absolutely reliable at 7,000 rpm. The only engine trouble we ever had followed accident damage and loss of lubricant.”

Lotus founder Colin Chapman was famous for focusing on making his cars lighter, as his mantra was “adding power makes you faster on the straights, subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere.”. This applied directly to the Type 105 project, with removal of anything not essential for racing: side glass, third brake lights, electric window assemblies, heater/air conditioner, and interior trim.

The Type 105 race car was developed from the Esprit with the following changes:

- Lotus Excel type front spoiler

- Glass sunroof replaced with fixed panel

- Plexiglass side windows

- Removal of all interior trim, sound deadening, AC/heating, spare wheel

- Original wire loom replaced with simpler loom

- Chassis was not galvanized (unlike road cars), which saved 17.6 lbs

- Thinner fiberglass panels (doors, roof, bonnet and engine decklid)

- Balanced and blueprinted engine

- Removal of high-pressure fuel pump

- larger injectors to increase fuel delivery

- Re-programmed ECM

- External pump and transmission oil cooler added in the rear valence

- All emissions system removed (required to keep exhaust diameter and routing)

- Open pipe exhaust replaced the cat/muffler

- 6-point roll cage, fitted to the suspension towers and to the frame behind the seats

- Car lowered 20 mm

- Limited-slip differential

- Stiffer springs (50% front, 25% rear)

- Specially-tuned Monroe shocks

- Stiffer bushings

- Revolution 3-piece wheels (8½ × 16 front; 9½ × 16 rear)

- Goodyear Eagle “S” tires (225/50ZR16 front, 255/50ZR16 rear)

- Braking system replaced with AP Racing 13" (front) and 12" (rear) discs from the Lotus Carlton

- 4-piston alloy calipers

- Extra brake cooling ducts

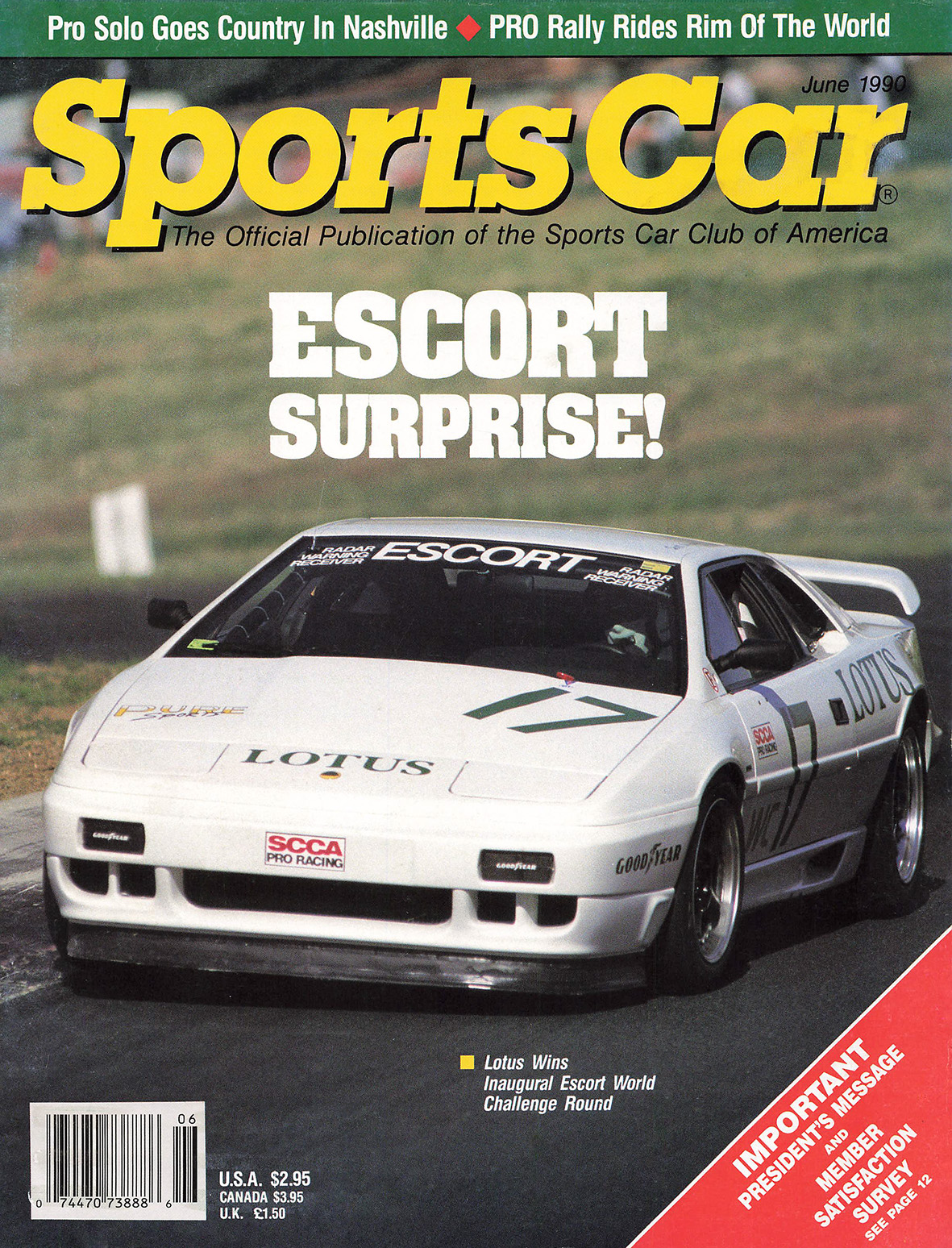

From the very start, the Type 105 Esprit quickly proved successful, surprising the competitors enough to appear on the cover of the SCCA magazine after winning its inaugural race on May 5, 1990 at Sears Point.

Lotus used the World Challenge series as a test bed for the Esprit’s upcoming ABS system. At the Laguna Seca race, one of the Type 105s was fitted with the new Lotus-designed three channel ABS system, while the other Type 105 ran without ABS. The Esprit fitted with ABS outperformed the non-ABS car, and from Road Atlanta onwards both cars were fitted with the system.

SCCA used a weight handicapping system for World Challenge, hence the minimum weight of the Lotus was raised after successive wins.

Immediately competitive, the duo of Doc Bundy and Scott Lagasse managed 6 poles and won 4 of 8 World Challenge races that season. Unfortunately, a late season crash stole Bundy’s opportunity to clinch the series championship. To celebrate its US racing success—and to homologate aerodynamic parts for the 1991 racing season—Lotus decided to produce a handful of road-going Esprits nearly identical to the race cars, adding only minimal comforts such as sport seats, glass windows, heat/AC, radio, and a galvanized chassis. Another season passed until Bundy was able win the championship in 1992, thus crowning the X180R as the last Lotus racing model to take a major racing championship.

For World Challenge race specification, the Type 105 modifications to the Turbo SE included:

- Wheel width can change (diameter must remain the same)

- 3 foot long exhaust on the Type 105

- Minor suspension tweaking (allowed)

World Challenge manufacturers could add any parts to the car, as long as they had an official manufacturer part number. For Lotus this included the front spoiler lip extension and the much larger disc brakes from the Lotus Carlton/Omega four door sedan.

The rules allowed for use of future production options, in this case the ABS braking system developed by Lotus for Delco Moraine to manufacture for introduction on the 1991 Esprit SE.

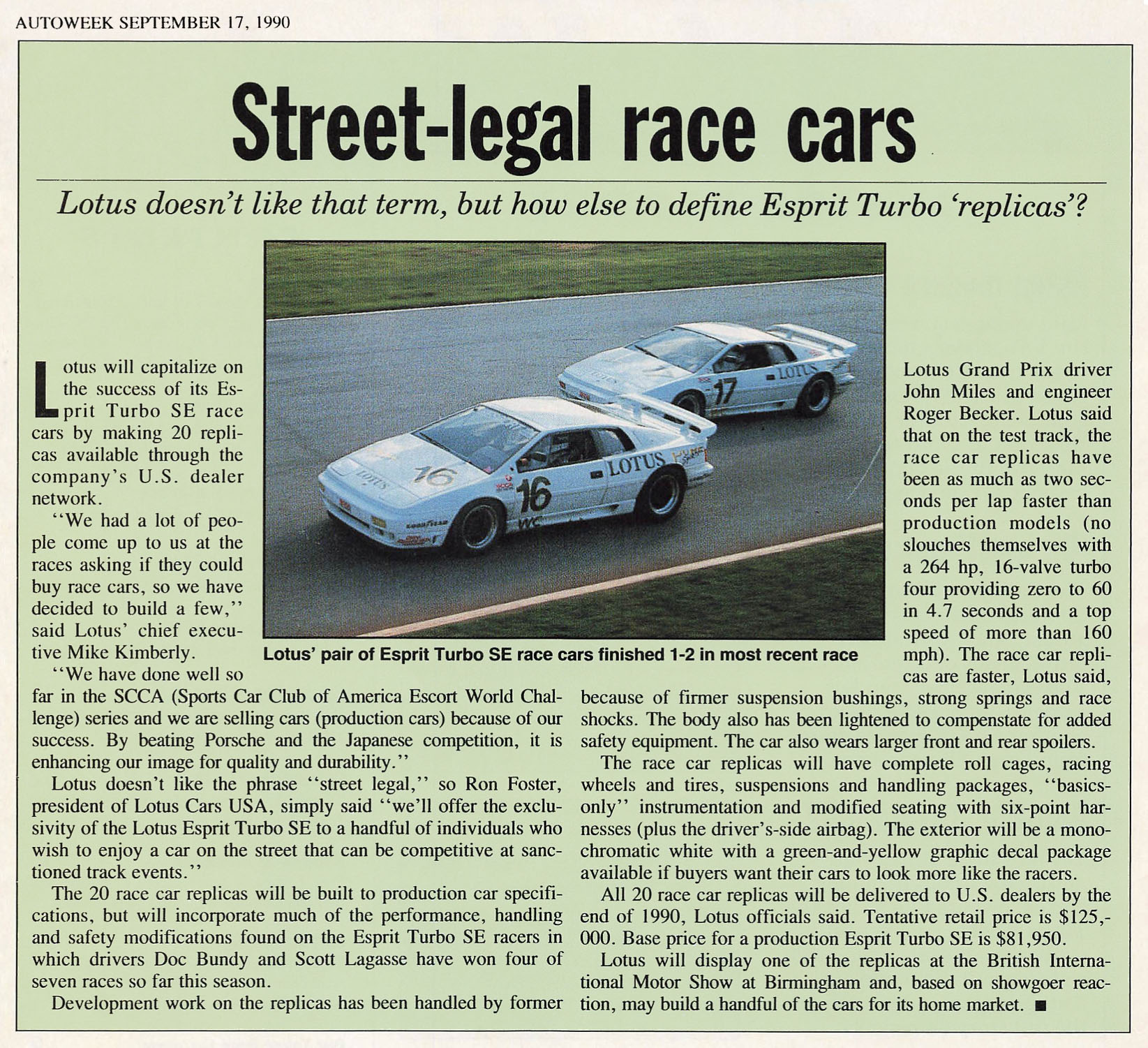

Type 105 Success Leads to the Supercar Series

With great success out of the box during the 1990 World Challenge racing season, the stage was set for Lotus to continue racing in North America. As luck would have it, a new series for high-performance production sports cars was being developed by the International Motor Sports Association of America (IMSA). However, the Type 105 Esprit race cars could not meet IMSA’s homologation requirements, since the car was too far developed beyond any Esprit equipment that Lotus offered to the public.

IMSA’s Competition Rules rules required manufacturers to have produced a minimum of 200 nearly identical road cars to the United States in order to campaign a race car, which the existing Steven’s Esprit production had already surpassed over the previous years. However, the homologation rules further required that the manufacturer further produce a minimum of 20 cars which shared the critical components of the “production” race car. Jack Ansley, "[The] IMSA series tried to do the best it could at keeping the cars relatively stock, but these were X180-R Esprits, a race-built version of the Esprit SE. Lotus produced 20 of them and sold them as street cars, the number needed in order that they’d be legal to race in the Bridgestone Series." Lotus scrambled to quickly produce a short run of just enough X180Rs to satisfy homologation requirements to race the Esprit in IMSA’s inaugaral Bridgestone Potenza Supercar Championship for the 1991 season.

IMSA’s competition rules required manufacturers to produce a minimum of 200 nearly identical road cars sold in the United States in order to campaign a race car, which the existing Peter Steven’s designed Esprit production car had already surpassed over the previous years. However, the homologation rules further required that the manufacturer further produce a minimum of 20 cars which shared the critical components of the “production” race car. According to Jack Ansley, The “IMSA series tried to do the best it could at keeping the cars relatively stock, but these were X180-R Esprits, a race-built version of the Esprit SE. Lotus produced 20 of them and sold them as street cars, the number needed in order that they’d be legal to race in the Bridgestone Series." Lotus scrambled to quickly produce a short run of just enough X180Rs to satisfy homologation requirements to race the Esprit in IMSA’s inaugural Bridgestone Potenza Supercar Championship for the 1991 season.

Marketing

How would they sell such a specialized and unique Esprit? Would buyers even be interested in such a departure from a luxury high-performance sportscar that the Esprit represented? Why build exactly twenty? Why only available in North America? And why produce a run of cars all at once instead of testing the waters with customers actually ordering cars ahead of time? These are all important details as to why the X180R was actually built. Celebrating its World Challenge success the prior year was only part of the rationale.

Lotus actually had an urgent need to produce these cars, and quickly, since the homologation deadline for preparing a car for the new IMSA Supercar series was looming. IMSA homologation requirements dictated that at least 20 cars nearly identical to any entered race car had to be manufactured for the North American market by December 31st of the year prior to the first racing season in which a car was campaigned. Otherwise, the car would be ineligible for competition until the following season. As part of the Bridgestone Supercar Championship requirements, at least twenty of the homologation cars were required to be road legal in North America. Lotus wasn’t the only manufacturer to build exactly 20 cars for this homologation process….Porsche followed suite, building exactly 20 of the 911 Turbo S2 to homologate the car with which Hurley Haywood would go on to win the IMSA Bridgestone Supercar Champsionship in 1991 and 1993. While Lotus erred on the side of building the most complete replica of the race car that could legitimiately be road registered, Porsche took a different approach by offering a more street focused base model S2 without any roll cage and racing harnesses. Even further, Porsche partnered with ANDIAL, effectively the Porsche Motorsports arm in the US at the time, to import the cars without the upgraded engine and turbocharger as they did not comply with EPA regulations at the time. Instead, importer ANDIAL would swap out the engines on all twenty cars with an already homologated Porsche engine upgrade package once they had cleared all the regulatory import hurdles, and before the cars were delivered to dealerships.

But how to sell such a departure to North American customers who were used to the Esprit being a high-performance luxury sportscar? Well, coming off a successful racing success with the Type 105, marketing had an ingenious idea to explain the racing replica car to potential buyers: name the X180R the World Challenge edition.

Lotus Designer Oliver Winterbottom specified several options for the X180R, which were removed prior to the series of X180Rs being assembled. These included racing seat belts (which the NHTSA would not have approved for use in the US) and an oil pan baffle.

Highlights from IMSA’s Supercar series from the 1994 IMSA Code Racing Regulations:

designed to encourage race competition of street legal exotic sports cars, to demonstrate the relative speed and excitement created by these makes

produced at a rate of at least 200 units in a 12-month period, described and published in manufacturer’s catalogs, marketed in the U.S. and available for purchase through the manufacturer’s dealer organizations, and bearing the manufacturer’s serial numbers designed for the eligible model year." “Model variants introduced after the first race of the season will not be approved until next season.

entrants are required to have in their possession at each event the official factory shop manual for the make and model of their car(s) in order to verify standard components and configurations.

Each car must conform strictly to its standard configuration as delivered to U.S. buyers by the manufacturer except where these rules allow or require specific modifications.

Roll Cage - Must be a welded cage” … “The roll cage must be fabricated from seamless mild steel tubing, bolted or welded to the chassis.

air conditioning components and associated parts may be removed

The regulations allowed manufacturers to sell a car without a roll cage, fuel cell, safety harness, safety window net, and fire extinguisher. However, shock absorbers must be the same, though they could be swapped as long as they were “interchangeable with the originals without any modifications. Wheels must be “as delivered”, however by the 1992 season the Lotus team was allowed to run 17” rear wheels.

Lotus Esprit X180R mandatory tire sizes in 1994 were: 225/50-16 (f) and 275/40-17 (r), and minimum weight was 2,800 pounds for 1994 versus the Porsche Turbo S2 at 3,200 pounds.

ADDITIONAL NOTES

Seattle, Washington, was a hotspot for the X180R when it was new. At the time, the Seattle area had two Lotus dealerships—Bayside Lotus, located downtown and owned by renowned Porsche racer Bruce Leven, and another Bellevue Lotus on the Eastside. At least five of the 20 X180Rs—25% of the entire production run—ended up in Seattle, either brand-new or shortly after their initial sale. A major factor in this was Microsoft, where employees were cashing in on stock options to participate in racing and track days.Additionally, LotuSport was also working to secure sponsorship from McCaw Cellular for its IMSA team. The McCaw brothers were passionate car enthusiasts, and Bruce McCaw would go on to establish the PacWest IndyCar team a few years later. Recognizing this enthusiasm, Lotus hosted an event at Pacific Raceways in Kent, WA, where LotuSport flew in Doc Bundy and another Lotus driver to take customers on hot laps in the X180R.

The primary focus by Lotus when developing and constructing the X180R homologation cars was performance, with assembly fit and finish taking a backseat as it was designed primarily for the track. However, in the North America market where all X180Rs were destined, buyers and dealers expected both high performance and flawless craftsmanship for a $128,000 car, these shortcomings became an issue. Even on new X180Rs, the perforated center console often appeared wavy and hastily trimmed. Complaints arose about inconsistencies in the Monaco White paint, with one major Lotus dealer even appealing to the company after receiving a brand-new car with several mismatched shades, making it difficult to sell. Dealers frequently had to touch up damage that occurred during shipping or manufacturing with dealer reports showing many areas of gel failure, paint sagging, etc that were corrected at bodyshops before delivering to customers. Once on the road, the X180R’s fabric seats also proved problematic, wearing out quickly and showing signs of fabric pulling after minimal use.

As part of the full IMSA weekend, the Bridgestone Supercar Championship included a 30-minute televised race.

For 1991, each Bridgestone Supercar Championship supported a prestige Camel GT championship race. The total prize fund was significant, at $375,000.

Each sports car had its minimum weight adjusted over time. Engines had to remain standard, though IMSA allowed blueprinting the engine to gain increased power and reliability through precise machining and assembly. Unlike other production car series, IMSA allowed the removal of catalytic convertors, and their replacement with straight pipes, which ensured that spectators enjoyed the mechanical symphony of the engines. As the name of the series suggested, all contenders running in the Bridgestone-sponsored series raced on shaved-down street-legal Bridgestone Potenza tires.

Development of the X180R Homologation Car

IMSA racing regulations for the Bridgestone Supercar series specifically stated that “model variants introduced after the first race of the season will not be approved until next season.” Technically, Lotus had until the first Lime Rock race on May 27, 1991, to introduce the car. Development was well underway by October 1990, with the homologation car internally dubbed at Lotus the “World Challenge Race Car Replica.” Oliver Winterbottom managed the X180R project with engineer Dave Minter responsible for all the technical details to build the car, and with engineer/driver John Miles and engineer Roger Becker as part of the team.

While a six-month lead time to meet IMSA’s requirements was reasonable, the real pressure cooker for Lotus Engineering was a new tax law in the United States that potentially jeopardized the entire racing program. IMSA required that all twenty of the homologation cars were to be sold in the North American market and a new United States 10% luxury car tax would become effective on January 1, 1991. Winterbottom commented in his book, A Life in Car Design –Jaguar, Lotus, TVR, “The [X180R] prototype was finished in late October 1990, and all the cars needed to be landed in the USA before the end of the year, to avoid the forthcoming luxury tax. We just managed it.” Had the X180R project been delayed even by a few weeks, the cost of purchasing an X180R would have increased by approximately $12,800, possibly killing any viability of selling a homologation race car and along with it any chance to race competitively in IMSA’s Supercar series.

The purpose of the X180R was clearly explained in the its Owner’s Handbook Supplement: “This special edition model has been designed as a fully road going ‘replica’ of the successful Lotus Esprit SCCA racing car, with certain changes made in order to comply with emissions regulations and other legal requirements.”

Fitted with a steel roll cage approved by the RAC, the X180R had 20 percent more torsional stiffness than an Esprit SE, while still shaving approximately 300 pounds from its weight. Aerodynamic changes included a different rear wing mounted further back, a front spoiler, and flared fenders. Unlike the Type 105, the ride height of the X180R was lowered by 10mm, instead of 20mm.

The X180R maintained the race car feel with a nomex-like “doeskin” interior material, though added a federally mandatory air bag steering wheel. Through oversized fuel injectors, reprogrammed ECU, redesigned exhaust system, and increased boost to 1 bar (14.5psi), the X180R’s Type 910S 4-cylinder engine added 46 hp over the base Esprit model, yielding 286 hp. The racing versions used even larger Lotus Carlton injectors. Additional mechanical upgrades included beefier suspension, a ZF clutch-type Limited Slip Differential, modified brakes, replacing the fog lamps with brake cooling ducts, and larger 16” aluminum 3-piece Revolution wheels.

All of this development translated into a 0-60 mph in 4.6 seconds, 0-100 mph in under 12 seconds, and a 170 mph top speed. While today the X180R is considered the holy grail of Esprit models, its MSRP in 1991 of $126,000 (approximately $300,000 in 2025 dollars) scared away many potential buyers, with the X180R tending to sit in dealerships awaiting a lucky new owner who understood how special it was.

The X180R homologation cars featured additional items that never appeared on the Type 105 World Challenge race cars, like the flared front fenders.

Type 106 — The IMSA Supercar

While the Type 105 was campaigned with great success in SCCA Pro World Challenge, significant improvements would need to be be undertaken for it to be competitive against the other factory backed teams like the Jacksonville, Florida, based Brumos Porsche team.

Modifications that differentiated the Type 106 from the X180R included a more-complex FIA-approved roll cage. Regulations also allowed for 17-inch rear wheels for IMSA and WC competition. Greater power was also tapped through the use of larger Lotus Carlton injectors.

Although hardly a performance enhancement, the iconic multi-color neon colored decals on the mirrors, windshield stripe and rear wing were added mid-season 1991. The addition was conceived by Doc Bundy to make the cars easier to identify on track.

One key to the X180R’s on track performance was the grunt of the turbocharged engine. According to Jack Ansley:

"[The X180R had] an advertised 285hp to start with from the factory. Remember, though, we were looking at being competitive with Porsche, which was running the 911 Turbo. We were limited under the rules to stock boost pressure, but we still managed to routinely get 450hp out of the engines. I think the most we ever got in a dyno test was around 525hp, just trying to see what it could take. That’s from a 2.2-liter four that was rated at 160hp before it was turbocharged. Race days, we were generally running 450 to 475hp, in a car that we got into the 1,900s, weight-wise."

Interestingly, when protested by other IMSA competitors in 1992 that the X180R may not be quite like the production car, Ansley responded that the cars being raced were “1992 model X180Rs”, running a different turbocharger for these 1992 varients under part number 525.4021.603AF.

Competition Follows Suit

To homologate a suitable 911 to campaign in IMSA’S Bridgestone Supercar Challenge, Porsche produced exactly 20 examples of its contender the 964 Turbo S2, in keeping with what Lotus had done with its X180R. While the 1991 964 RS N-GT would have been an excellent option for the Supercar Challenge, except it was developed beyond what would have been feasible to actually sell for road use in the United States.

Unlike the stripped down and race-ready Lotus X180R, Porsche did not push the envelope as far with the 964 Turbo S2 homologation specials with the cars being sold to customers without a factory roll cage, racing seat belts, or spartan interior. Porsche still had painful memories of lengthy battles with the DOT and EPA over its attempt to import the 959 Sport (959S) under a non-road going race car exemption. The US was a critical market for Porsche’s financial success, and being denied import of a supercar they had heavily invested in was a painful lesson. Thus Porsche was wary of trying to bring in a modified production road-going car, especially since homologation required that the vehicles be capable of licensing for street use.

Not to be thwarted from a chance at racing Porsches in a major televised series, Porsche racing driver Hans Stuck and Alwin Springer, then president of Porsche Motorsports North America and owner of the famous ANDIAL tuner, hatched a plan with Porsche. Porsche would build and export twenty as well 20 fully-optioned USA-spec 964 Turbo homologation specials directly to ANDIAL. The 964 Turbo S2 left Porsche’s Stuttgart factory with minimal engine preparation, as the Type M30/69 3.3L turbo-charged racing engine would not pass EPA import requirements. Once the 2,822 lb homologation cars arrived at ANDIAL they would install an already homologated “retrofit” power kit provided by Porsche, before being distributed to dealers. By the time the 964 Turbo S2 reached customers at 18 dealerships in the United States, and two in Canada, the added power kit increased the base sticker price by $10,065 USD—to $119,005—before any other options were included.

While technically legal by IMSA’s own rule book, as the Monroney window sticker for the 964 Turbo S2 included a “S2” notation, this was pushing the boundaries. The conversion included different turbocharger, intercooler, camshafts, cylinder head gasket, along with adjusting valve lifts, clearances, and timing. Porsche was allowed to compete with the S2, and secured the championship after winning four of the seven races during 1991. Lotus took home one win since it only ran the last three races of the season. However, the irony is thick, as IMSA and Porsche later protested that David Murray’s Lotus X180R had a swapped turbocharger after his 1993 Lime Rock race win.

X180R for Europe

During a meeting with all its European importers in late 1990, Lotus Sales Director Mike Bishop set the first discussion agenda to pitch an “ultra high performance Esprit.” Bishop was looking for dealer feedback to gauge interest on whether any would be open to offer the X180R “Race Replica” within their markets. A coil binder similar to the X180R Owner’s Manual Supplement was prepared for the meeting and included internal discussion points for the importers. The materials presented to the dealers included the Winterbottom letter on the X180R and all the X180R technical specifications sheets. The pitch highlighted that 20 had been commissioned and “sold” by Lotus Cars USA, and stated that: “the opportunity now exists to build some for other markets if there is a demand.” The the X180R offered in Europe was to be identical to the North American market version, except for “a European non airbag steering wheel is fitted, the vehicle is fitted with knee restraint and the airbag sensor system.” Buyers who purchased one of the X180Rs would include “customer tuition on the track” as well as a seat “fitting” at the Lotus Factory in Hethel.

The importer’s purchase price from the factory was to be £55,000 (approximately $78,500 USD), with each European importer setting an adjusted final price, with appropriate markup, in the currency corresponding to the market. The notes for the pitch ended, touting: “JUST LOOK AT THAT MARGIN & LOOK AT THE CAR…” Interestingly, the pitch mentioned that Lotus had built an additional X180R race replica for customer demonstrations at the Hethel test track. Whether this additional X180R still exists is unknown. While the reasons are unknown, none of the European Lotus importers/dealers decided to offer the race-focused X180R. Perhaps they caught wind of Lotus Cars USA’s difficulties in selling such an expensive niche car.

Sport 300 – X180R’s Successor

While European Lotus importers declined the X180R, the more comfort oriented Esprit Sport 300 was offered in 1993. While similar to the X180R, its base specifications positioned it as more of a high performance track car than as an out and out race car. The Sport 300 chassis was not as stiff as the X180R, as it lacked the full roll cage mated directly to the chassis. However, the 300’s rigidity was significantly more than a standard Esprit thanks to its four-point braced frame. The optional LotusSport competition package took the car close to the original X180R racing roots, including adding a full bolt-in roll cage, racing seat belts, and a fire extinguisher. Capable of 0-60 mph in 4.7 seconds, and 0-100 mph in 11.7 seconds, the performance was not quite on par with the X180R. The Sport 300 name was derived from the model’s 300+ horsepower the four-cylinder 910S engine produced when the Garrett turbocharger was on full boost.

Having achieved great racing success in America, Lotus decided to campaign Esprits at Le Mans. They turned to the Sport 300 as the basis for development, entering a pair of Sport 300 Turbos in 1993 and 1994. Unfortunately in both years, success evaded Lotus due to overheating issues when cars were brought in for driver and tire changes. Lotus ultimately produced 64 Sport 300s over the two-year production period.

Appendix: People

Lotus

- Roger Becker, Lotus development engineer for the Type 105 race car

- Oliver Winterbottom, Lotus manager for the X180R road-going project

- Dave Minter, Lotus chief engineer for the X180R

- Alan Nobbs, Lotus powertrain engineer for racing team (hired from Corvette ZR-1 project)

- John Miles, Lotus chassis development (former Lotus F1 driver)

- Colin Marriott, Lotus engineer helping with chassis, engine, etc

- Roger Becker, Lotus chassis engineering director

- Richard Clarke, Lotus Cars USA field engineer (previously worked for Lotus Engineering in active F1 suspensions)

- Ed Aspinall, Lotus engineer helping LotuSport

- Arnie Johnson, Lotus Cars USA, Vice President/Technical Services (promoted to CEO in 1997)

- Mike Bishop, Lotus Sales Director, pitched the X180R concept for European markets

LotuSport Team

- Jack Ansley, Team owner (previously Pure Sports)

- Joe Grassi, Team Crew Chief (7 years)

- Ed Webber, Crew/Car Chief

- Ed Wheeler, Crew/Car Chief

- Walk Puckett, Crew/Car Chief

- Jeremy Buckingham, Crew

- Buddy Epps, Marketing

- David Arner, Marketing

- Neil Nierenberg, Transporter (1992 season)

- Ron Shelton, Transporter

- Alan Nobbs

- David Simkin

Drivers

- Doc Bundy, LotuSport lead driver (1990-1995)

- Scott Lagasse, LotuSport driver

- Andy Pilgrim, LotuSport driver

- Paul Newman, LotuSport driver

- Mike Brockman

- Bo Lemler

- Bobby Carradine

- Steve Hansen, sponsor/driver

Corrections and Photo Request

We would welcome any additional photos, info, setup sheets, corrections, etc about the history of the Lotus Esprit X180R. There is still much unknown behind the scenes of the action during this racing program. Please contact info@lotus-x180r.com.